Persons, Collections and Topics

Hitchcock-Chase

The Hitchcock-Chase Collection of Grass Drawings consists of 2,713 drawings (mostly ink, but some pencil) of grasses, representing hundreds of genera, assembled by Smithsonian Institution agrostologists Albert Spear Hitchcock (1865–1935) and Mary Agnes Chase (1869–1963). Curated by the Art Department, the collection is on indefinite loan to Hunt Institute from the Smithsonian and is, to our knowledge, the only such collection of grass illustrations. Some of the illustrations in this collection were reproduced in Hitchcock's Manual of the Grasses of the United States (1935, 1950 with Chase), Manual of the Grasses of the West Indies (1936) and "North American species of Agrostis" (1905); in Chase's "The North American species of Paspalum" (1929); in Frank Lamson-Scribner's "American grasses (illustrated)" (1897); and in Jason R. Swallen's The Grasses of British Honduras and the Petén, Guatemala (1936). The Hitchcock-Chase Collection features botanical illustrations by Chase, Hitchcock, A. H. Baldwin, (Miss) M. D. Baker, Mary Wright Gill, Frank Lamson-Scribner (1851–1938), Theodore Holm, Leta Hughey, Benjamin Y. Morrison (1891–1966), Mrs. George M. Mullett, W. R. Scholl, Frances Carnes Weintraub, Edna May Whitehorn and unidentified artists.

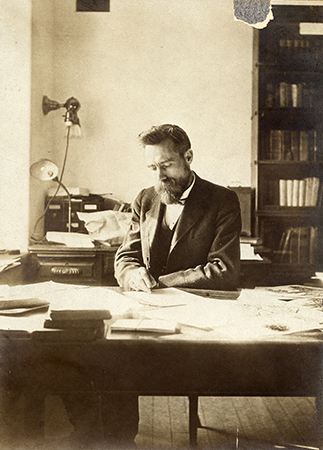

Albert Spear Hitchcock

Botanical explorer and systematic agrostologist Albert Spear Hitchcock was born in Owosso, Michigan, on 4 September 1865 and grew up in Kansas and Nebraska. Although he had long been interested in plants and studied botany under Charles E. Bessey (1845–1915), he earned a B.S. in agriculture (1884) and an M.S. in chemistry (1886) at Iowa Agricultural College (now Iowa State University of Science and Technology), teaching chemistry there from 1886 to 1889. When he could no longer resist the lure of botany as a full-time occupation, he accepted positions as librarian and curator of the herbarium at the Missouri Botanical Garden and instructor in the Engelmann School of Botany at Washington University (1889–1891).

In 1890 he married Rania Belle Dailey, with whom he had five children. He moved to Kansas State Agricultural College in Manhattan, where from 1892 to 1901 he was a professor of botany and botanist to the Experiment Station. During this period he began to travel extensively, seeking types of grasses for his research on the world's grass genera. Floyd A. McClure (1897–1970) wrote that Hitchcock's "field work was not perfunctory...and he set a rare example in the intimacy with which he penetrated the private life of the plants he studied. At the same time, his love of the grasses was so spontaneous and so strong that he never wasted an opportunity to extend his knowledge of them" (1936).

Hitchcock's colleague Mary Agnes Chase knew well his dedication to his science, recounting in her 1936 eulogy of Hitchcock how he had once walked 242 miles in 24 consecutive days and camped at night, all the while toting a special wheelbarrow he had designed especially for botanizing. On the subject of Hitchcock's fieldwork in the salt marshes of the Gulf Coast, Chase recounted that Hitchcock remarked: "I waded through water almost up to my knees, pushed my wheelbarrow, and still managed to keep my collection dry. The mosquitoes were very bad. I had to put on my coat, put cheesecloth around my head and a pair of extra socks on my hands. My shoes had worn through and my feet were blistered.... But, for all the discomforts, the collecting was magnificent, and I felt fully repaid" (Chase 1936). The fruits of this period's botanical labors were over 80 papers, including papers on grasses and the flora of Kansas and Experiment Station bulletins and circulars.

In 1901 Hitchcock became assistant chief in the United States Department of Agriculture's Division of Agrostology in Washington, D.C., and in 1905 he was promoted to systematic agrostologist at the USDA and also appointed custodian of the newly established Section of Grasses; Chase assumed the custodianship of the grass herbarium at Hitchcock's death (Morton and Stern 1966). The USDA made the grass collection a priority, and Hitchcock built upon the work of his predecessors George Vasey (1822–1893) and Frank Lamson-Scribner. Determined to build the grass collection and "insatiably eager to see every part of the earth" (Chase 1936), Hitchcock visited every state in the United States, as well as the West Indies, Cuba, Alaska, Canada, Mexico, the Philippines, Japan and China, and traveled throughout Africa, Indochina, Central and South America. In 1928 he was promoted to principal botanist in charge of systematic agrostology in the USDA.

From 1905 on he filled 45 field books with notes and published extensively on Gramineae, authoring over 250 works, several jointly with Chase. His publications included A Text-Book of Grasses (1914), "The genera of the grasses of the United States" (1920), Methods of Descriptive Systematic Botany (1925), Manual of the Grasses of the United States (1935, 1950 with Chase) and Manual of the Grasses of the West Indies (1936), and monographs of the American species of Agrostis (1905), Leptochloa (1903), Panicum (1910 with Chase) and Aristida (1924).

In addition to his ongoing botanical exploration, collection and scholarship, Hitchcock played an active role in many American and international botanical societies and committees, including the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the National Research Council, the Botanical Society of America, the Organization Committee for Biological Research of the National Research Council, and the Executive Committee of the Institute for Research in Tropical America. Special notice should be given to his work on botanical nomenclature, where his practical views often contributed to international agreement on divisive subjects.

Hitchcock died of heart failure on 16 December 1935 at sea on board the steamer City of Norfolk while returning home with his wife from Europe, where he had attended the Sixth International Botanical Congress in Amsterdam, visited many European herbaria in preparation for a work on the grass genera of the world and celebrated his 70th birthday. Hitchcock was held in high esteem by his peers and colleagues: "[H]e was a lovable and unassuming man. To the student of systematic botany who knew only his work, he was a tireless and productive student of a technically difficult and to many botanists quite uninteresting group of plants, the grasses. His contribution to our understanding of this economically most important family of plants has been unequalled in America" (Fernald 1937). Enriched by the hundreds of thousands of specimens acquired by Hitchcock and Chase throughout their collaborative careers, the Smithsonian Institution's grass herbarium became the largest and one of the most complete such grass collections in the world. Hitchcock and Chase also bequeathed to the Smithsonian in 1928 their private agrostological library; among its 6,000 books and pamphlets were Linnaean titles, early systematic works and rare books on the grasses.

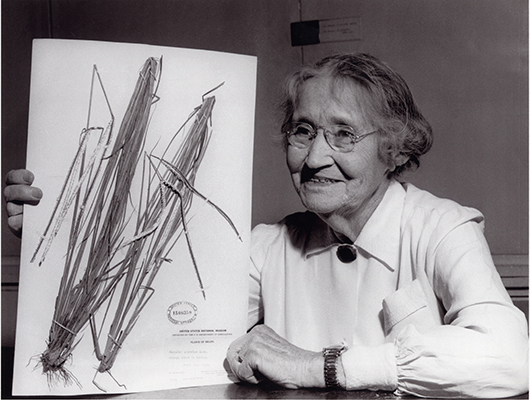

Mary Agnes Chase

Born Mary Agnes Meara in Iroquois County, Illinois, on 20 April 1869 (the family's name changed to Merrill after 1871), Chase was educated in Chicago. Interested in botany from an early age, she supported herself by proofreading for newspapers (including the School Herald, whose editor, William Ingraham Chase, she married in 1888; she was widowed less than a year later and never remarried) and collected plants in her free time. While collecting northern Illinois and Indiana flora in the mid-1890s, she became acquainted with bryologist Ellsworth Jerome Hill (1833–1917), who hired her to illustrate some of the species he was describing. This friendship and experience as an illustrator led to her association with Charles Frederick Millspaugh (1854–1923) of the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. While working as a meat inspector in the Chicago stockyards, she moonlighted as a botanical illustrator, depicting species in Gramineae, Cyperaceae and Compositae for Millspaugh's "Plantae Utowanae" (1900) and "Plantae Yucatanae" (1903–1904).

At Hill's suggestion, Chase took a civil-service exam to apply for a botanical artist position at the USDA. In 1903 she moved to Washington, D.C., to begin working in the Division of Forage Plants. The Division was later transferred from the USDA to the Smithsonian Institution, and while working in the grass herbarium she began a series of papers on Paniceae (1906–1911). She met Hitchcock at the herbarium and began collaborating with him, assisting him as illustrator and botanist over the 30-year period in which she worked first as a scientific assistant in systematic agrostology (1907), later as assistant botanist (1923) and then as associate botanist (1925). At Hitchcock's death in 1935, she succeeded him as senior botanist in charge of systematic agrostology and as custodian of the herbarium.

Chase collected grasses along the eastern and southern coasts and in the southwestern states of the United States and in Europe, northern Mexico, Puerto Rico, Venezuela and Brazil, including "two journeys across South America alone, during which she went by train, boat, donkey, and by foot, became the only woman to stand on top the highest mountain in South America, braved insects that bored into her toes, ran out of food and got hungry..." (Schultz 1949). She spent 7 months in Brazil and added 500 species to the herbarium as a result of her fieldwork there. Her 1897–1959 bound field books are at the Smithsonian. She explained her long-standing interest in grasses by noting grasses' prominence in the Bible: "Grass is what holds the earth together. Grass made it possible for the human race to abandon cave life and follow herds. Civilization was based on grass, everywhere in the world" (Schultz 1949).

Because many of the plants she collected were new to science, information about them was eagerly incorporated by Hitchcock into his definitive works, especially Manual of the Grasses of the United States (which she later revised), and her own 70 publications, which included monographs on various grass genera and First Book of Grasses (1922). Chase also completed the Index to Grass Species (1962), which had been worked on over the years by Lamson-Scribner, E. D. Merrill (1876–1956), F. T. Hubbard (1875–1962) and C. D. Niles (1886–?), and she published its three volumes (containing 80,000 entries) at the age of 93. Her discoveries made the Smithsonian's grass herbarium a resource for taxonomic research on American grasses, and her research led to the development by agricultural scientists of more nutritious and disease-resistant food crops. Chase also made time—and made news—for her suffragette activities and was even jailed in 1918 and 1919 for her speeches and protests.

Although she formally retired from the USDA in 1939, she continued to work at the National Herbarium, without pay, for the rest of her life, during which time she visited Venezuela to assist its Department of Agriculture in developing a range-management program. The certificate of merit for distinguished achievement in botanical science that the Botanical Society of America awarded her in 1956 was followed two years later by an honorary doctorate granted by the University of Illinois—her first and only degree, at the age of 89. The Smithsonian made her an honorary fellow, and the Linnean Society of London elected her as a fellow in 1961. She died in Bethesda, Maryland, of congestive heart failure on 24 September 1963 at the age of 94.

Bibliography

Chase, M. A. 1906–1911. Notes on genera of Paniceae. Proc. Biol. Soc. Washington 19: 183–192; 21: 1–10; 21: 175–188; 24: 103–159.

Chase, M. A. 1922. First Book of Grasses: The Structure of Grasses Explained for Beginners. New York: Macmillan.

Chase, M. A. 1929. The North American species of Paspalum. Contr. U.S. Natl. Herb. 28(1): 1–310.

Chase, M. A. 1936. [Hitchcock eulogy typescript delivered at annual meeting of Botanical Society of Washington, 1 Dec. 1936.] Depository: A. S. Hitchcock Biographical Files, folder 1, Archives, Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation, Pittsburgh, Pa.

Chase, M. A. and C. D. Niles, comps. 1962. Index to Grass Species. 3 vols. Boston: G. K. Hall.

Fernald, M. L. 1937. Albert Spear Hitchcock. Proc. Amer. Acad. Arts Sci. 71(10): 505–506.

Griffiths, D. 1912. The grama grasses: Bouteloua and related genera. Contr. U.S. Natl. Herb. 14(3): 343–428.

Hitchcock, A. S. 1903. North American species of Leptochloa. Bull. Bur. Pl. Industr. U.S.D.A. 33: 1–24.

Hitchcock, A. S. 1905. North American species of Agrostis. Bull. Bur. Pl. Industr. U.S.D.A. 68: 1–68.

Hitchcock, A. S. 1914. A Text-Book of Grasses with Special Reference to the Economic Species of the United States. New York: Macmillan.

Hitchcock, A. S. 1920. The genera of grasses of the United States with special reference to the economic species. Bull. U.S.D.A. 772: 1–307.

Hitchcock, A. S. 1924. The North American species of Aristida. Contr. U.S. Natl. Herb. 22(7): 517–586.

Hitchcock, A. S. 1925. Methods of Descriptive Systematic Botany. New York: Wiley.

Hitchcock, A. S. 1935. Manual of the Grasses of the United States. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

Hitchcock, A. S. 1936. Manual of the Grasses of the West Indies. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. [U.S.D.A., Misc. Publ. 243.]

Hitchcock, A. S. and A. Chase. 1910. The North American species of Panicum. Contr. U.S. Natl. Herb. 15: 1–396.

Hitchcock, A. S. and A. Chase. 1950. Manual of the Grasses of the United States, ed. 2. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. [U.S.D.A., Misc. Publ. 200.]

Lamson-Scribner, F. 1897. American grasses (illustrated). Bull. Div. Agrostol. U.S.D.A. 7: 1–331.

McClure, F. A. 1936. Dr. Albert Spear Hitchcock—An appreciation. Lingnan Sci. J. 15(2): 305–306.

Millspaugh, C. F. 1900. Plantae Utowanae. Publ. Field Columb. Mus., Bot. Ser. 2(1): 1–110; 2(2): 111–134.

Millspaugh, C. F. 1903–1904. Plantae Yucatanae. Publ. Field Columb. Mus., Bot. Ser. 3(1): 1–84; 3(2): 85–151.

Morton, C. V. and W. L. Stern. 1966. The United States National Herbarium. Pl. Sci. Bull. 12(2): 1–8.

Schultz, E. 1949. 79-year-old Washingtonian is foremost authority on grass. St. Louis (Missouri) Star-Times 10 March.

Swallen, J. R. 1936. The Grasses of British Honduras and the Petén, Guatemala. Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington. [Bot. Maya Area Misc. Pap. 9.]

The Hitchcock-Chase Collection images are in the public domain and can be downloaded from the Catalogue of the Botanical Art Collection at the Hunt Institute: Digital Public Domain Images database. To locate these images in the database, search on an artist's last name or Hitchcock-Chase Collection. When using these images, please include the following credit statement: Hitchcock-Chase Collection of Grass Drawings, courtesy of the Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pa., on indefinite loan from the Smithsonian Institution. The artworks also are available for on-site viewing by researchers; please contact the Art Department for additional information or to arrange a visit.

Other resources

For thumbnails of the Hitchcock-Chase Collection images, see the Catalogue of the Botanical Art Collection at the Hunt Institute database.

For information about portraits of and biographical citations for Hitchcock and Chase, see the Hunt Institute Archives Register of Botanical Biography and Iconography database.

See the Smithsonian for information about its current research on grass and Hitchcock's 1900–1920s field books and Chase's 1897–1959 field books.

![Enlarge <p>Bromus porteri [<em>Bromus anomalus</em> E. Founier, Poaceae alt. Gramineae], ink on paper by A. H. Baldwin, 19 × 13 cm, Hitchcock-Chase Collection of Grass Drawings, on indefinite loan from the Smithsonian Institution, HI Art accession no. 6010.0134.</p>](/admin/uploads/hibd-baldwin-bromus_001.jpg)

![<p>Bouteloua megapotamica (Spreng.) Kuntze [<em>Bouteloua megapotamica</em> (Sprengel) Kuntze, Poaceae alt. Gramineae], ink on paper by Mary Agnes Chase (1869–1963), 29 × 26 cm, for David Griffiths (1867–1935), "The grama grasses: Bouteloua and related genera" in <em>Contributions from the United States National Herbarium</em> (1912, fig. 52), Hitchcock-Chase Collection of Grass Drawings, on indefinite loan from the Smithsonian Institution, HI Art accession no. 6010.0825.</p>](/admin/uploads/hibd-chase-bouteloua_001.jpg)

![<p>[<em>Agrostis</em> Linnaeus, Poaceae alt. Gramineae], ink on paper by Albert Spear Hitchcock (1865–1935), 29 × 20.5 cm, Hitchcock-Chase Collection of Grass Drawings, on indefinite loan from the Smithsonian Institution, HI Art accession no. 6010.0088.</p>](/admin/uploads/hibd-hitchcock-agrostis_001.jpg)