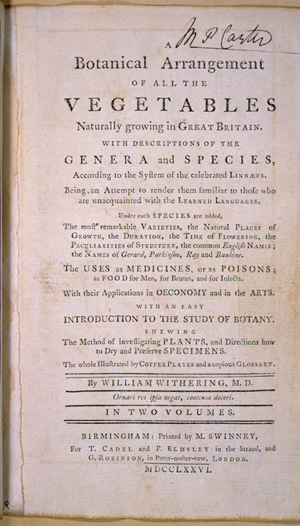

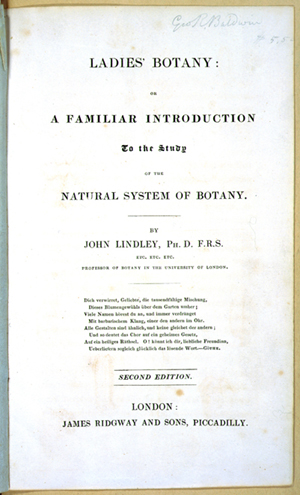

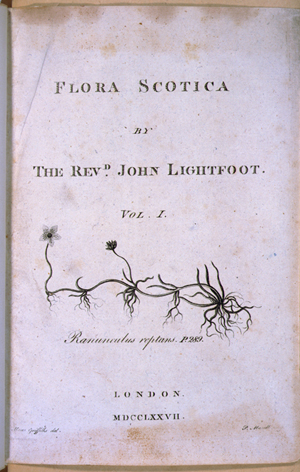

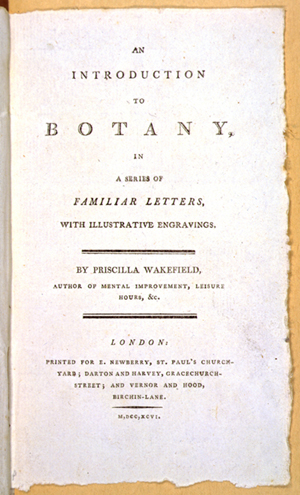

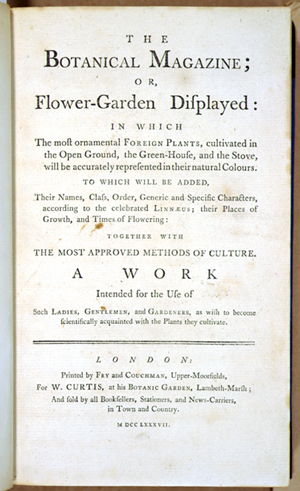

Linnaeus, as the father of taxonomy or systematic botany, planted the germ for a scheme that is within reach not only of professional botanists but also of amateurs — authors, clergymen, gardeners, painters, wildflower enthusiasts, and others. Some professionals published Linnaeus’ ideas for a popular audience, and in turn many enlightened amateurs through their own field work and publications have disseminated Linnaeus’ ideas to a far wider section of the population, sometimes making important contributions to science along the way. The literature in this case demonstrates not only the breadth and variety of Linnaeus’ influence in the British Isles during the late 18th and early 19th centuries but also how the dissemination of his ideas there opened the world of botany to a wide range of interested naturalists, reaching beyond professionals to include amateurs of all kinds, and even children.