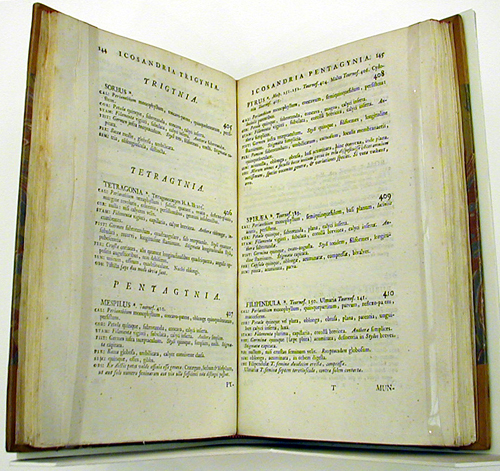

Linnaeus divided the plant kingdom into 24 classes, each of which he named according to the number of stamens and their arrangement in the flowers. In Ehret’s engraved plate these classes are represented by the 24 letters of the Latin alphabet. In Ehret’s original drawing for the plate, preserved in the Natural History Museum in London, he has written the name of the plant he had chosen as an example of each particular class, but only for the first ten and last four classes. Each of the first ten classes (A–K) are named according to the number of stamens, beginning with Monandria (one stamen), Diandria (two stamens), etc. up to Decandria (ten stamens). The flowers in the eleventh (L) class, Dodecandria, have 12–19 stamens. The following four classes (M–P) are characterized not only by the number of stamens but also by their position; the four classes (Q–T) have stamens united in a bundle or phalanx, the next three classes (V–Y) have stamens and pistils in separate flowers. The whole is completed with Cryptogamia (Z), which are plants without proper flowers. For this class Ehret chose the fig as an example.

Linnaeus included Ehret’s Tabella in his Genera Plantarum without credit to the artist, provoking the response, "When he was a beginner [Linnaeus] appropriated everything for himself which he heard of, to make himself famous" (Blunt, The Compleat Naturalist, New York, 1971, p. 107). Nevertheless, Ehret probably met Linnaeus again when the latter visited London for a month.

Carolus Linnaeus, portrait by J. H. Scheffel, 1739. This portrait is known as the "bridegroom portrait"; Scheffel also painted a portrait of Sara Lisa Moraea as Linnaeus' bride in the same year. HI Archives portrait no. 47c. |

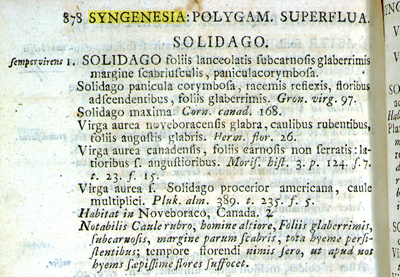

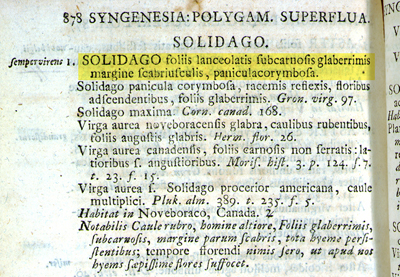

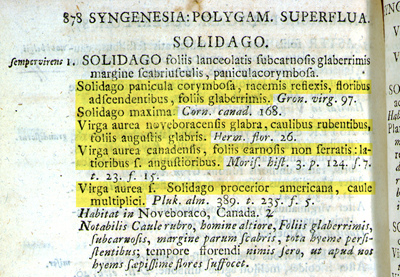

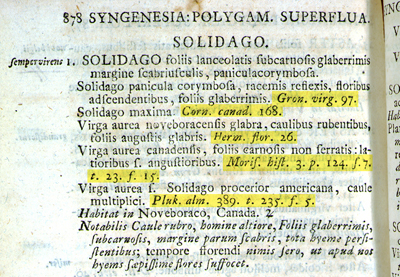

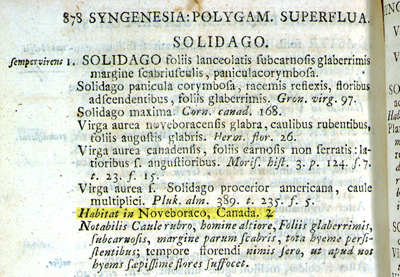

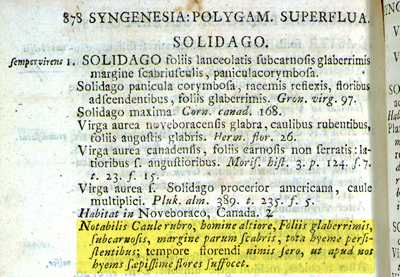

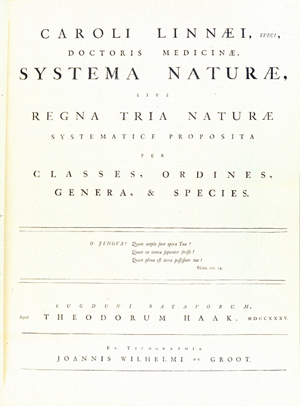

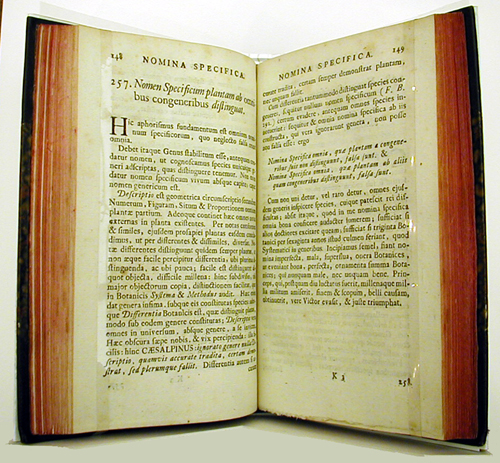

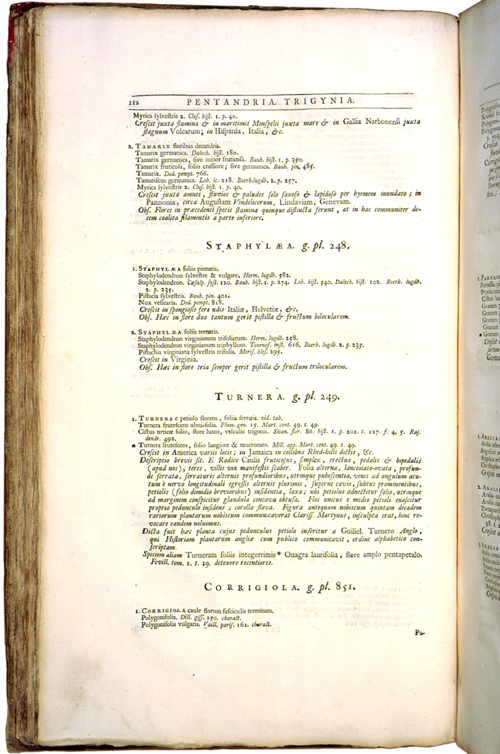

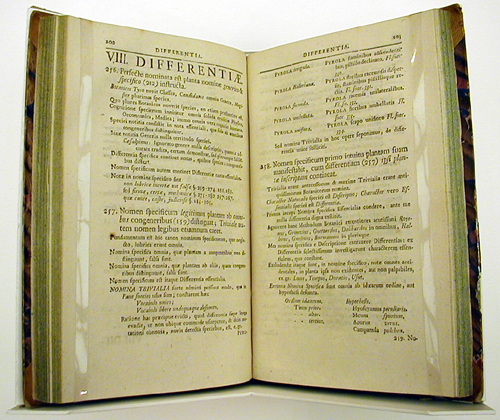

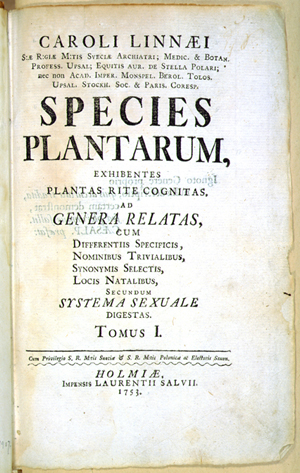

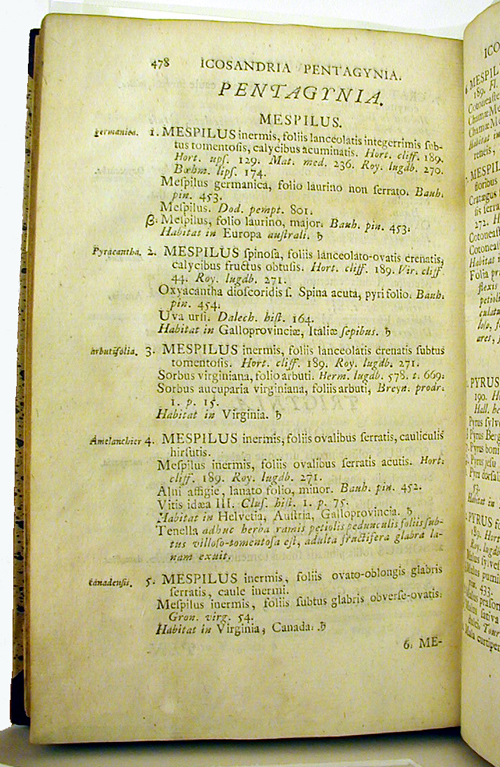

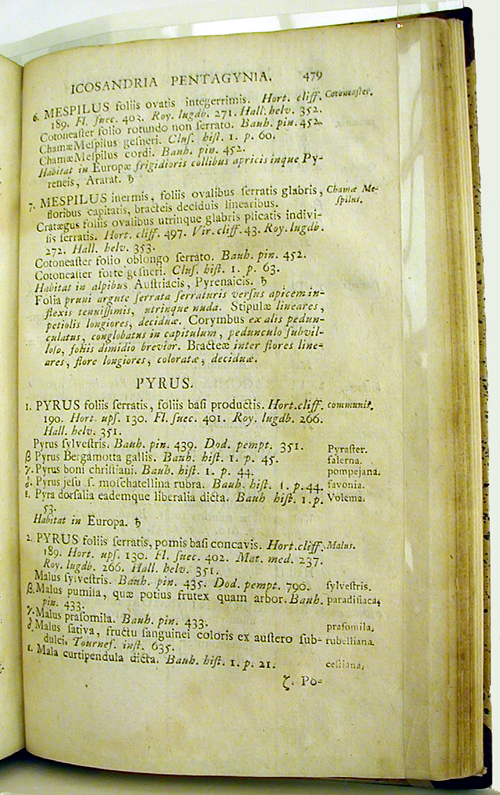

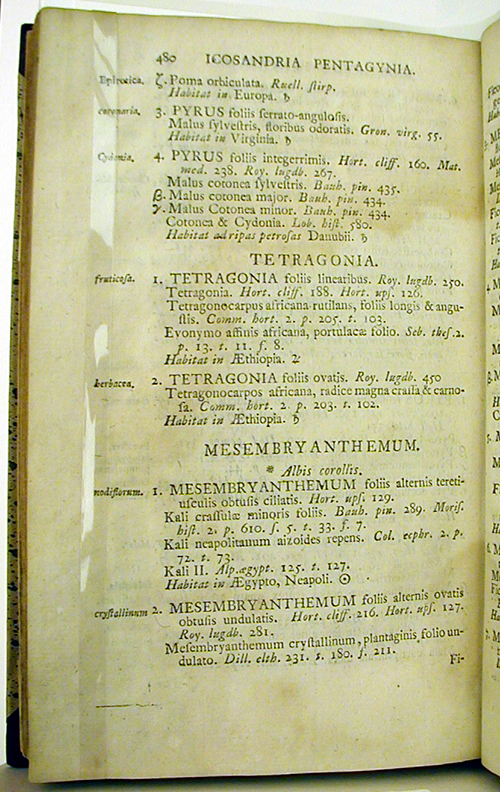

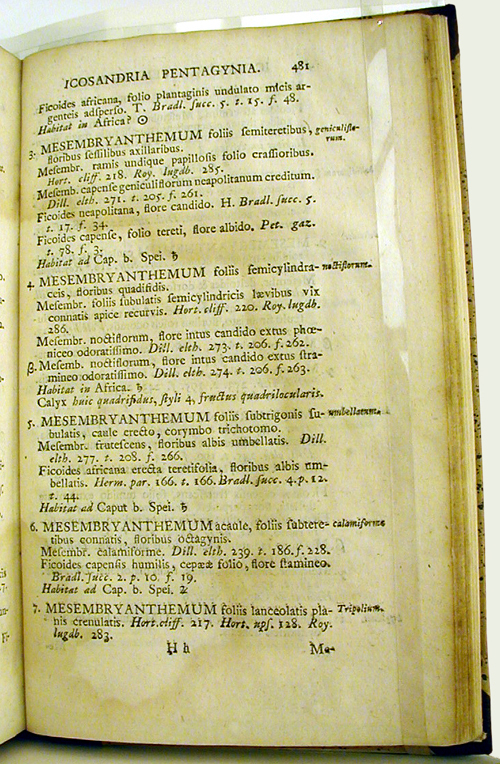

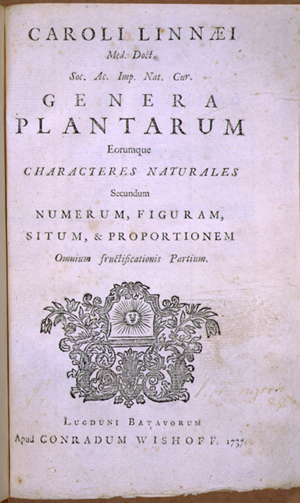

The essence of Linnaeus’ achievement is that he succeeded in regularizing the way plants and animals were studied. He did this by developing a system of uniform description, classification and naming, which in turn simplified and facilitated the work of identifying plants and animals. He also brought together the work of previous generations and unraveled complicated descriptions in their writings to sort out what was known and to arrange it all in his new system. Others before him had done similar work, but not on such a grand scale, and not so comprehensively. His classification system generally fell out of use within a century of its creation, but his system of naming plants and animals is still in use today and has provided the world with what became, in effect, a universal scientific language. He also developed a standard order to be followed in writing descriptions, so that the parts of a description would be used consistently in every description in which they were needed. Several features of his system can be seen in this sample entry from page 878 of Species Plantarum (below).

The essence of Linnaeus’ achievement is that he succeeded in regularizing the way plants and animals were studied. He did this by developing a system of uniform description, classification and naming, which in turn simplified and facilitated the work of identifying plants and animals. He also brought together the work of previous generations and unraveled complicated descriptions in their writings to sort out what was known and to arrange it all in his new system. Others before him had done similar work, but not on such a grand scale, and not so comprehensively. His classification system generally fell out of use within a century of its creation, but his system of naming plants and animals is still in use today and has provided the world with what became, in effect, a universal scientific language. He also developed a standard order to be followed in writing descriptions, so that the parts of a description would be used consistently in every description in which they were needed. Several features of his system can be seen in this sample entry from page 878 of Species Plantarum (below).