Map of Mediterranean.

Detail of plate 73 from John Bartholomew, ed., The Times Atlas of the World: Vol. 4, Southern Europe and Africa (London, 1956). © Bartholomew Ltd 2002 Reproduced by Kind Permission of HarperCollins Publishers www.bartholomewmaps.com

(see this image enlarged)

The places of the odyssey of knowledge in the Mediterranean and European world: classical culture, born in ancient Greece (Athens, fifth century B.C. and Alexandria from the third century B.C.), emigrated toward Rome principally during the first centuries B.C.–A.D. Then, it was transferred to Constantinople (created in 332) and moved again to the West, with late antique translations (fifth–sixth centuries, probably in Ravenna) and, later on, to the Arabic world (from the ninth century), in Baghdad. This body of knowledge, progressively augmented by the different cultures that received it, arrived again in the West, in Southern Italy (Salerno), where Arabic treatises were translated into Latin from the end of the 11th century. Transmitted until the Renaissance, it was also known directly from the Greek originals at that time in centers such as Padua and Venice, Florence and Rome, then to be further reproduced by printing, starting in Germany and then in centers like Köln and Augsburg.

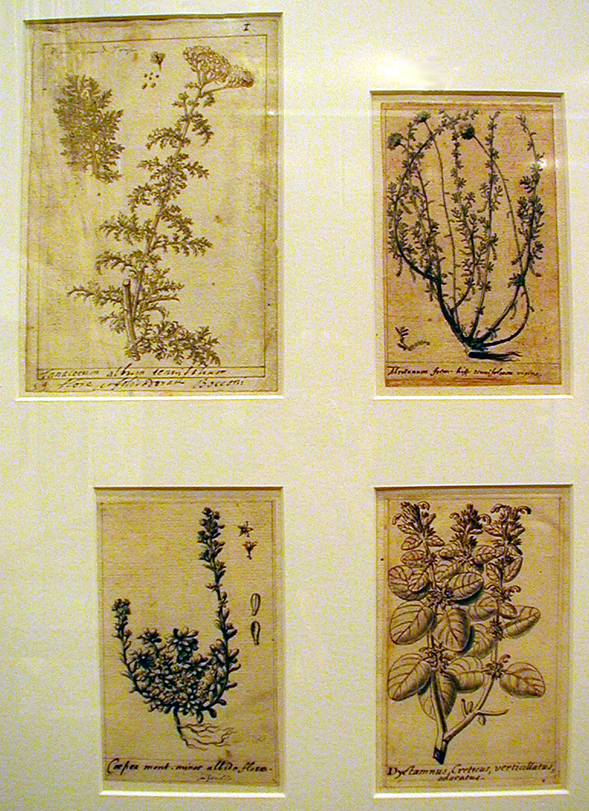

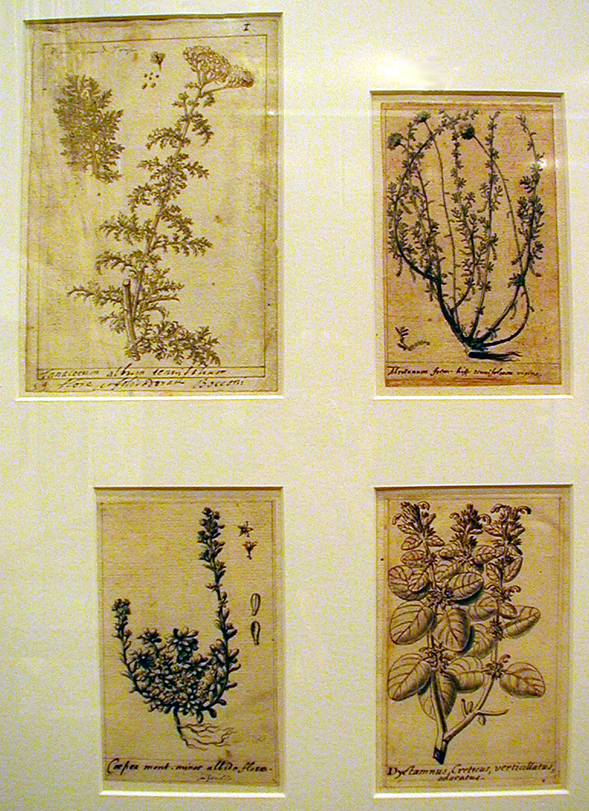

In 1737 in Paris, Linnaeus met the noted French botanical painter Claude Aubriet (1665–1742) and his student Madeleine Françoise Basseporte (1701–1780), both court flower painters. Aubriet had accompanied the French botanist Joseph Pitton de Tournefort to Levant in 1700.

Top Right:

Abrotanum foem. hisp. tenuifolium virens [Abrotanum], ink drawing with wash attributed to Claude Aubriet (1665–1742) for Jacques Barrelier’s (also Jacobo Barreliero, 1606–1673) Plantae per Galliam, Hispaniam et Italiam Observatae, Iconobus Aeneis Exhibitae (Paris, 1714, pl. 429).

Bottom Right:

Dyctamnus Creticus, verticillatus, odoratus [Dictamnus], ink drawing with wash attributed to Claude Aubriet (1665–1742) for Jacques Barrelier’s (Jacobo Barreliero, 1606–1673) Plantae per Galliam, Hispaniam et Italiam Observatae, Iconobus Aeneis Exhibitae (Paris, 1714, pl. 130).

Top Left:

Tanacetum album tenuifolium … [Tanacetum], ink drawing with wash attributed to Claude Aubriet (1665–1742).

Bottom Left:

Coepea mont. minor albida flore [Sedum], ink drawing with wash attributed to Claude Aubriet (1665–1742) for Jacques Barrelier’s (Jacobo Barreliero, 1606–1673) Plantae per Galliam, Hispaniam et Italiam Observatae, Iconobus Aeneis Exhibitae (Paris, 1714, pl. 1170).

Melo Vulgaris [Cucumis melos L., Muskmelon], engraving (restrike) by Nicolas Robert (1614–1685) from Dionys Dodart’s (1634–1707), Recueil des Plantes Gravée par Ordre du Roi Louis XIV (Paris, 1788). Print by Chalcography Department, Louvre Museum.

The outstanding 17th-century French botanical artist Nicolas Robert did most of the drawings and many of the engravings for the three magnificent volumes of Recueil des Plantes Gravée par Ordre du Roi Louis XIV. Because of the vicissitudes of Louis XIV’s wars, this landmark of botanical illustration was not published until 1788, a century after its inception and almost a decade after Linnaeus’ death.

|

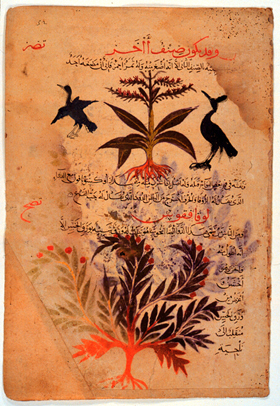

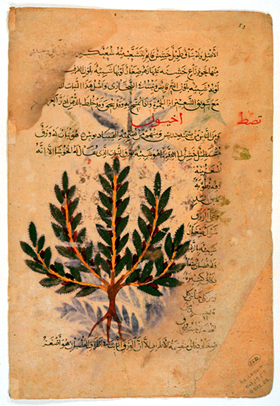

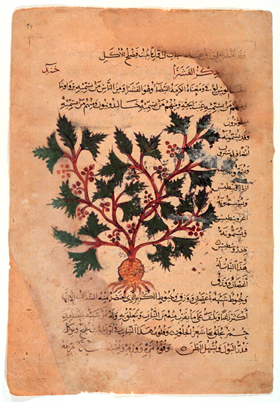

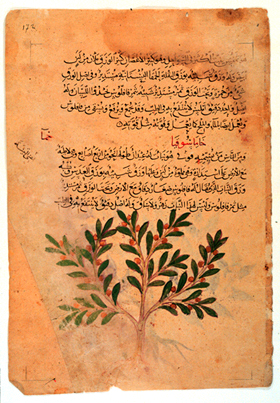

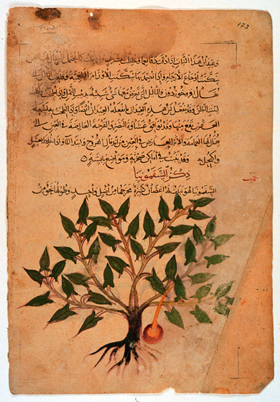

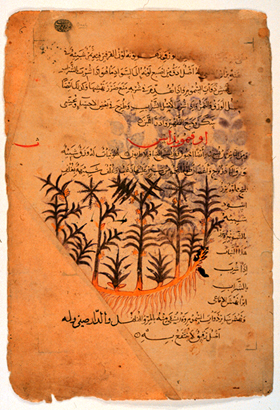

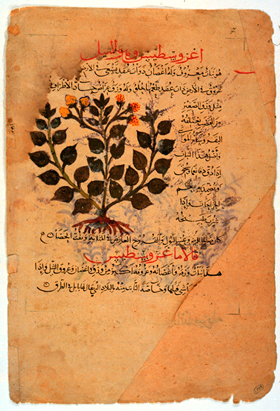

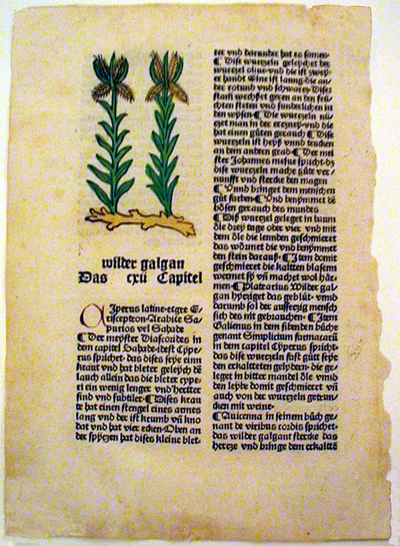

The scientific works of classical antiquity were written on papyrus and reproduced by hand, from one copy to another, in a long chain of transmission. Over time, however, the shape and construction of the book changed: papyrus, first used in the form of a roll, was then transformed into a book in the current shape. Then, papyrus itself was supplanted by parchment, a material that is more flexible and less delicate than papyrus. Finally, paper was introduced: created in China, it was first transferred to the Arabic world and, from there, to Byzantium and the West. At the same time, texts were transmitted through all the cultures that flourished around the Mediterranean Sea. Transmitted without interruption from classical antiquity to the Byzantine world after the foundation of Constantinople in 330, some texts were first translated into Latin during the fifth and sixth centuries. Then, a large part of the Greek scientific heritage was recovered in the Arabic world from the ninth century onwards, and, in turn, these Arabic versions were translated into Latin in the West from the end of the 11th century onwards. The pieces in this showcase condense the history of the book and of the transmission of knowledge in the Mediterranean area.

The scientific works of classical antiquity were written on papyrus and reproduced by hand, from one copy to another, in a long chain of transmission. Over time, however, the shape and construction of the book changed: papyrus, first used in the form of a roll, was then transformed into a book in the current shape. Then, papyrus itself was supplanted by parchment, a material that is more flexible and less delicate than papyrus. Finally, paper was introduced: created in China, it was first transferred to the Arabic world and, from there, to Byzantium and the West. At the same time, texts were transmitted through all the cultures that flourished around the Mediterranean Sea. Transmitted without interruption from classical antiquity to the Byzantine world after the foundation of Constantinople in 330, some texts were first translated into Latin during the fifth and sixth centuries. Then, a large part of the Greek scientific heritage was recovered in the Arabic world from the ninth century onwards, and, in turn, these Arabic versions were translated into Latin in the West from the end of the 11th century onwards. The pieces in this showcase condense the history of the book and of the transmission of knowledge in the Mediterranean area.